TRANS + GENDER IDENTITY

TRANS + GENDER IDENTITY

There are a lot of different ways someone can express their gender or sex.

Gender identity isn’t an easy topic to understand, and sometimes we need to unlearn some of our old ideas about what it is so that we can really get what gender is all about. Most of us were taught that there are only two genders (man/masculine and woman/feminine) and two sexes (male and female). However, there is a lot more to it than that.

Transgender Identities

When we’re born, a doctor assigns us a sex. This has to do with our biology, chromosomes, and physical body. Male babies are generally assumed to be “men” and female babies are generally assumed to be “women.” Some people never question their assigned gender or sex, and choose to identify with what they were assigned at birth – that’s called being “cisgender.” But there are others who do question their gender or sex, and that’s completely normal and ok.

If you don’t feel that your gender identity – meaning, your own personal sense of what your gender is – matches the gender you were assigned at birth, you might identify as transgender (or trans). In addition to being a gender identity, transgender is also an umbrella term that includes many other labels, like genderqueer and gender non-conforming.

Genderqueer and gender non-conforming identities describe someone whose gender expression is, or seems to be, different from their assigned gender role. Usually, genderqueer and gender non-conforming people avoid gender-specific pronouns like “she/her” and “he/him,” and use more neutral pronouns instead. It’s important to note that not all genderqueer or gender non-conforming people identify as transgender, even though they fall under the umbrella of diverse gender identities.

Are you questioning your gender, and aren’t sure what feels right to you? Don’t worry. You are not alone! Consider a few of these questions, taken from our “Coming Out As You ” guide.

- How do you feel about your birth gender?

- What gender do you wish people saw you as?

- How would you like to express your gender?

- What pronouns (like he/him or she/hers, or ze/zir or they/them) do you feel most comfortable using?

- When you imagine your future, what gender are you?

Remember, there are many parts to our gender, including:

- Gender Expression: How we choose to express our gender in public. This includes things like our haircut, clothing, voice and body characteristics, and behavior.

- Gender Identity: Our personal sense of what our own gender is.

- Gender Presentation: How the world sees and understands your gender.

If you decide that your current gender or sex just isn’t right, you may want to make your gender identity fit with your ideal gender expression and presentation. This is called “transitioning,” and can include social (like telling other people about which pronouns you like), legal (like changing your name, officially), or medical (like taking hormones, or having surgery). You don’t have to go through all of these things to be “officially” transgender, or to have your gender identity be valid. It’s all up to you, and what feels safe and comfortable.

Using Proper Trans Terms

It’s very important to use appropriate terms when talking about the transgender community. For example, you may see the term transgender shortened with an asterisk (*) to include the many identities that fall under the transgender umbrella.

The term “transgender” should only be used as an adjective and never as a noun. Also, the term “Transgendered” is grammatically incorrect and should never be used. Other offensive words include: tranny, transvestite, she-male, he/she, lady man, shim, “it,” or transsexual*.

Example: My friend is transgender.

Example: I think I’m going to come out as a transgender man.

* Some transgender people prefer to identify as transsexual, although others consider it to be outdated. Always ask for, and use, the term that a person prefers.

Understanding Transphobia

Unfortunately, trans people often face hatred or fear just because of who they are. Even some LGB people may have transphobic feelings that can make it harder for them to support transgender people as they also fight for equality and acceptance. If you ever feel that you are a victim of a transphobic hate crime, please visit the Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund site.

Intersex Identities

Remember, sex does not equal gender – it’s actually an entirely different thing that relates to our biology and physical characteristics. Generally we think about sex as a binary: male and female. However, there are several conditions that a person can be born with that don’t fit the typical definitions of female or male. For example, a person might be born appearing to be female on the outside, but have mostly male anatomy on the inside. Or a person may be born with genitals that seem to be in-between the usual male and female types. Others may be born with “mosaic genetics,” so that some of their cells have XX chromosomes and some have XY. Sometimes intersex characteristics aren’t noticed until puberty, when our body goes through a lot of different changes.

Many intersex people are given a sex of male or female at birth, even if they fall somewhere in the middle. If you think you might be intersex, don’t worry. There are people out there who can help! Here is a comprehensive list of intersex conditions and related resources and support groups: http://www.isna.org/faq/conditions/know.

Talking About “Intersex”

Intersex is an adjective that describes a person. Intersex is never a noun or a verb, because no one can be “intersexing” or “intersexed.” You may have heard the word “hermaphrodite” from Greek mythology. Please don’t use this term, as it is archaic and offensive to intersex people.

Resources

Gender Identity

- Genderqueer Identities

- Gender Spectrum

- The Gender Book

- Students and Gender Identity Guide for Schools (USC Rossier’s, online MSC program)

Intersex

- Inter/Act – A youth group for young people with intersex conditions or DSD

- OII Intersex Network

- American Psychological Association – What does intersex mean?

Trans

- Trans Student Equality Resources

- Advocates for Youth – I think I might be transgender

- TransYouth Family Allies

- WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health)

- TransWhat? A guide towards allyship

- Resources for Transgender College Students

“Trans + Gender Identity.” The Trevor Project, 14 Apr. 2020, www.thetrevorproject.org/trvr_support_center/trans-gender-identity/.

RESEARCH BRIEF: PRONOUNS USAGE AMONG LGBTQ YOUTH

July 29, 2020

Summary

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth experience higher rates of mental health challenges compared to their cisgender, straight peers as a result of chronic stressors such as discrimination and victimization (Kann, et al., 2018; Johns, et al., 2019; Meyer, 2003). Pronouns, a way to streamline language, have historically emphasized a binary construction of gender in many languages, including English (Butler, 1999). While many people use a pronoun associated with their sex assigned at birth, gendered pronouns, and the assumptions behind them, may represent a daily stressor for LGBTQ youth, particularly youth who are transgender and nonbinary (TGNB). Affirming LGBTQ youth’s gender by using pronouns that align with their gender identity has been shown to improve mental health outcomes. Specifically, The Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health found that TGNB youth who reported having their pronouns respected by all or most of the people in the lives attempted suicide at half the rate of those who did not have their pronouns respected (The Trevor Project, 2020). This brief uses data from the Trevor Project’s 2020 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health to further explore pronoun usage among LGBTQ youth.

Results

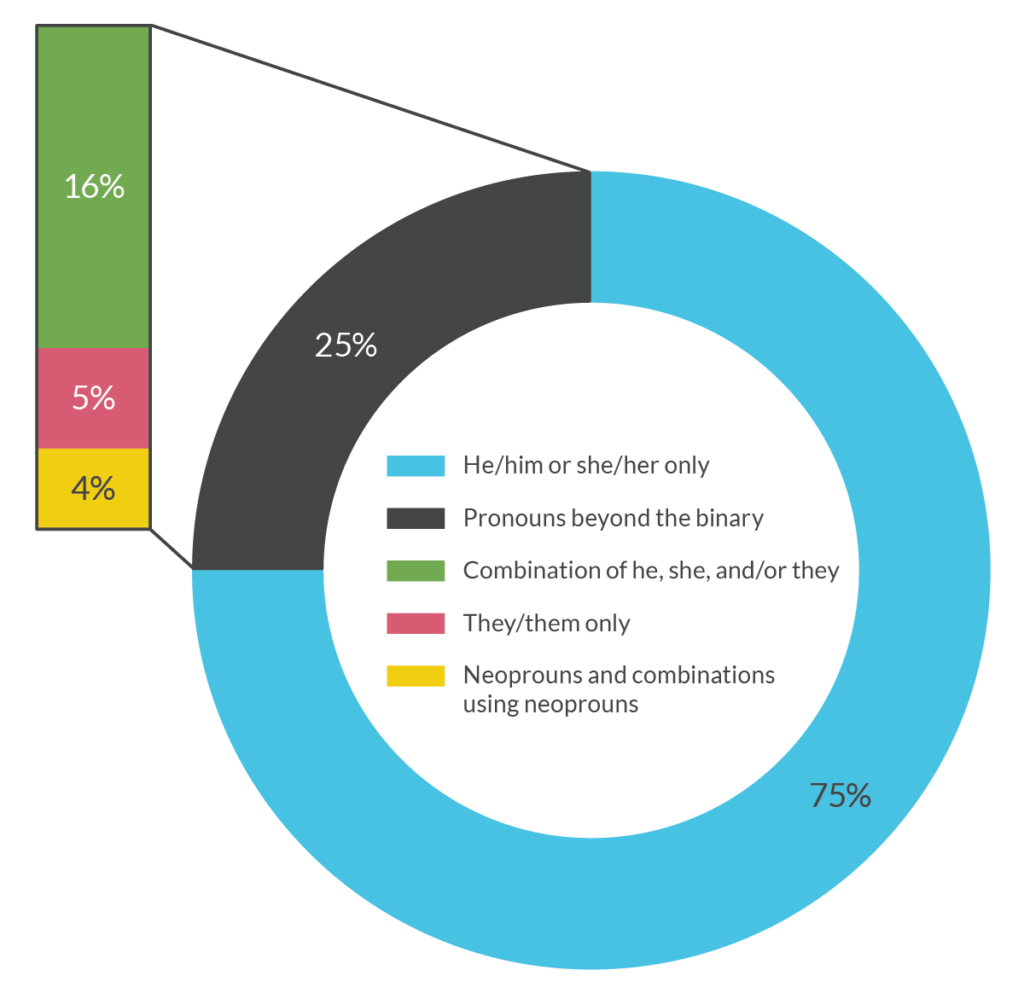

1 in 4 LGBTQ youth use pronouns or pronoun combinations that fall outside of the binary construction of gender. Although 75% of youth use either he/him or she/her exclusively, 25% of LGBTQ youth use they/them exclusively, a combination of he/him, she/her, or they/them, or neopronouns such as ze/zir or fae/faer.

Nearly two-thirds of LGBTQ youth who use pronouns outside of the binary opt to use combinations of he/him, she/her, and they/them. This included pronoun usage such as “she and they” or “he and they,” as well as using “she, he, and they” to express the nuances of their gender.

Some LGBTQ youth do use pronouns beyond those already familiar to most people. While 4% of LGBTQ youth reported the use of pronouns such as “ze/zir,” “xe/xim,” and “fae/faer,” or combinations of these terms with other pronouns, 96% of LBGTQ youth in our sample used pronouns that are familiar to most people by using either a combination of he/him, she/her, or they/them or one of these pronoun sets exclusively.

Methodology

A quantitative cross-sectional online survey was used to collect data between December 2019 and March 2020. LGBTQ youth ages 13–24 who resided in the U.S. were recruited via targeted ads on social media. The final analytic sample was 40,001 LGBTQ youth. All youth were asked, “Which pronouns do you currently use? Please select all that apply.” Response options included: “she, her, hers”; “he, him, his”; “they, them, theirs”; “ze, zir, zirs”; and “something else (please specify).” Although “ze, zir, zirs” was the only set of neopronouns provided outside of the “something else” category, it was only endorsed exclusively by 1% of the total sample.

Looking Ahead

The results show that although LGBTQ youth are using pronouns in nuanced ways, the majority who use pronouns outside of the gender binary use either familiar pronouns or combinations of these familiar pronouns to express their gender. An individual’s pronoun expression, or even the decision to avoid them altogether, is a very important reflection of a person’s identity. Respecting pronouns is part of creating a supportive and accepting environment, which impacts well-being and reduces suicide risk (Durwood et al., 2017; The Trevor Project, 2020). The Trevor Project Guide to Becoming an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Youth suggests that the best way to confirm a person’s pronouns is by asking or by introducing yourself with your pronouns, to give the person an opportunity to share theirs. Parents, other family members, school staff, health professionals, and other individuals in youth’s lives can best support youth by asking for and consistently using their pronouns. Affirming gender in school and workplace settings can begin by having a practice of sharing pronouns for everyone and setting the expectation that all individuals will have their pronouns respected by others.

“Research Brief: Pronouns Usage Among LGBTQ Youth.” The Trevor Project, 22 July 2020, www.thetrevorproject.org/2020/07/29/research-brief-pronouns-usage-among-lgbtq-youth/

Let’s Get it Right: Using Correct Pronouns and Names

We use people’s pronouns and names frequently and in regular, every day communication, both verbally and in writing. We do it almost without thinking. Because names and pronouns are the two ways people call and refer to others, they are personal and important. They are also key facets of our identity. Therefore, calling someone by the wrong name or “misgendering” them by using incorrect pronouns can feel disrespectful, harmful and even unsafe.

From an early age, many were taught that pronouns should follow specific rules along the gender binary: “she, her and hers” for girls and women and “he, him and his” for boys and men. However, as our society has progressed in understanding gender identity, our language must also be updated. It should be accurate and convey understanding and respect for all people, especially for those who are transgender, gender non-conforming and non-binary.

Because some people identify themselves outside the gender binary (gender binary is the idea that gender consists of two distinct, opposite and disconnected categories—male and female), it is important to make sure you know the specific pronouns people use, whether they use female, male or gender-neutral pronouns. Be mindful that the pronouns “he” and “she” come with a set of expectations and gender norms about how people express their identity. For many, these terms are limiting and confining so gender-neutral options are preferable.

If you use the wrong pronoun or name, people may not correct you because they may feel awkward, uncomfortable or unsafe. If you don’t know what people’s pronouns and names are, you can listen to how they or others refer to them, or you can ask. There are suggestions below about how to do this in a school or classroom setting.

There has been a much-needed movement away from asking and identifying pronouns as “preferred.” For example, people used to ask, “What is your preferred pronoun?” This question is problematic because a person’s pronouns are not just “preferred”—they are the pronouns that should be used.

Strategies for Supporting Young People

Using correct names and pronouns shows respect, acceptance and support to all students, especially those who are transgender, gender non-conforming and non-binary. While some schools and school districts have specific policies on a range of issues regarding transgender and gender non-conforming students, below are practical tips and strategies for showing respect to students.

Student Interest Survey

At the beginning of the school year or new semester, many teachers distribute a “get to know you survey” to learn more about their students: how they best learn, their hobbies/interests outside of school, what they did over the summer, etc. You can add a question about pronouns such as: "What are your gender pronouns?" or "Which pronouns do you use?" You can also ask what name they use. This sends a message that you want to know their accurate name and pronouns and it gives you the information you need to get it right. You should also ask whether it’s okay or not to use their name and pronoun in communication home to parents/family members and in parent-teacher conferences. Keep in mind that some students may not disclose this information to some or all family members.

Model Inclusivity

If you know students’ correct pronouns and names, use them in class and do not rely on “official” or roster information. You can act as a role model by sharing your pronouns and using them when introducing yourself. Be careful not to make assumptions about someone’s pronouns and name and at the same time, be sensitive to students who may not feel ready or comfortable to disclose this information. If you make a mistake in using the wrong name or pronoun, quickly self-correct and move on. Similarly, if another student or adult uses an incorrect name or pronoun, make the correction and continue the conversation. Don’t dwell unnecessarily on it, which could inadvertently make the student feel more uneasy.

One-on-one Conversations with Students

If you do not address names/pronouns in a survey or another way, students may talk with you individually after class about their name or pronoun. Listen to what they say without judgment, ask clarifying questions and let them know you will correctly use their name or pronoun. As stated above, the best way to ask is: "What are your gender pronouns?" or "Which pronouns do you use?" Be mindful that some students may not disclose this information at home so it’s helpful if you sensitively ask whether their name and/or pronoun should also be used in communication home to family members.

Discussion Starters

There are a few ways to start a discussion about the use of pronouns. Always be mindful not to single anyone out and don’t engage in a class discussion if you feel it would increase the discomfort, rather than minimize it.

One way is to have students read an article about the history of the pronoun “they” such as A Brief History of Singular "They" or Even the staunchest grammarians are now accepting the singular, gender-neutral “they.” Or you can have students read something like Here's Why Gender Pronouns Are So Important. There are also short videos that can serve as conversation starters about pronouns such as Why Gender Pronouns Matter or Why Pronouns Matter For Trans People. After you read or watch, ask open-end discussion questions like: What are your thoughts and feelings about what you read/watched? What did you learn that you didn’t know before? How are you thinking differently about this now? You could also assign a reflective writing assignment or a “quick write” to have students express their thoughts.

Confidentiality

Always be aware that while students may share their pronouns and name with you, this doesn’t mean they have shared it with other teachers, students, friends or family members. If you have the opportunity, ask students whether their pronouns and name should be used in communication home to parents or not. And don’t share this information without express permission from the students themselves.

List of Pronouns

Below is a list of pronouns. This is not a comprehensive list and other pronouns, or no pronouns at all, might be preferred by some transgender people. The correct pronouns for a person do not necessarily align with the associated gender identity or expression. Be mindful that cisgender as well as transgender, gender non-conforming and non-binary people may use feminine, masculine or gender-neutral pronouns.

Feminine: She, her, hers

Masculine: He, him, his

Gender Neutral: They*, them, their

Gender Neutral: Ze, zir, zirs

Gender Neutral: Ze, hir, hirs

* Many dictionaries have recognized “they” as a singular pronoun for years, including Oxford English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary and dictionary.com

Https://Www.adl.org/Education/Resources/Tools-and-Strategies/Lets-Get-It-Right-Using-Correct-Pronouns-and-Names?Gclid=EAIaIQobChMIk4Sjj8Cx7AIVBbLICh3d9wDWEAAYAiAAEgJWefD_BwE.

A brief history of singular ‘they’

Singular they has become the pronoun of choice to replace he and she in cases where the gender of the antecedent – the word the pronoun refers to – is unknown, irrelevant, or nonbinary, or where gender needs to be concealed. It’s the word we use for sentences like Everyone loves his mother.

But that’s nothing new. The Oxford English Dictionary traces singular they back to 1375, where it appears in the medieval romance William and the Werewolf. Except for the old-style language of that poem, its use of singular they to refer to an unnamed person seems very modern. Here’s the Middle English version: ‘Hastely hiȝed eche . . . þei neyȝþed so neiȝh . . . þere william & his worþi lef were liand i-fere.’ In modern English, that’s: ‘Each man hurried . . . till they drew near . . . where William and his darling were lying together.’

Since forms may exist in speech long before they’re written down, it’s likely that singular they was common even before the late fourteenth century. That makes an old form even older.

In the eighteenth century, grammarians began warning that singular they was an error because a plural pronoun can’t take a singular antecedent. They clearly forgot that singular you was a plural pronoun that had become singular as well. You functioned as a polite singular for centuries, but in the seventeenth century singular you replaced thou, thee, and thy, except for some dialect use. That change met with some resistance. In 1660, George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, wrote a whole book labeling anyone who used singular you an idiot or a fool. And eighteenth-century grammarians like Robert Lowth and Lindley Murray regularly tested students on thou as singular, you as plural, despite the fact that students used singular you when their teachers weren’t looking, and teachers used singular you when their students weren’t looking. Anyone who said thou and thee was seen as a fool and an idiot, or a Quaker, or at least hopelessly out of date.

Singular you has become normal and unremarkable. Also unremarkable are the royal we and, in countries without a monarchy, the editorial we: first-person plurals used regularly as singulars and nobody calling anyone an idiot and a fool. And singular they is well on its way to being normal and unremarkable as well. Toward the end of the twentieth century, language authorities began to approve the form. The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) not only accepts singular they, they also use the form in their definitions. And the New Oxford American Dictionary (Third Edition, 2010), calls singular they ‘generally accepted’ with indefinites, and ‘now common but less widely accepted’ with definite nouns, especially in formal contexts.

Not everyone is down with singular they. The well-respected Chicago Manual of Style still rejects singular they for formal writing, and just the other day a teacher told me that he still corrects students who use everyone … their in their papers, though he probably uses singular they when his students aren’t looking. Last Fall, a transgender Florida school teacher was removed from their fifth-grade classroom for asking their students to refer to them with the gender-neutral singular they. And two years ago, after the Diversity Office at the University of Tennessee suggested that teachers ask their students, ‘What’s your pronoun?’ because some students might prefer an invented nonbinary pronoun like zie or something more conventional, like singular they, the Tennessee state legislature passed a law banning the use of taxpayer dollars for gender-neutral pronouns, despite the fact that no one knows how much a pronoun actually costs.

It’s no surprise that Tennessee, the state that banned the teaching of evolution in 1925, also failed to stop the evolution of English one hundred years later, because the fight against singular they was already lost by the time eighteenth-century critics began objecting to it. In 1794, a contributor to the New Bedford Medley mansplains to three women that the singular they they used in an earlier essay in the newspaper was grammatically incorrect and does no ‘honor to themselves, or the female sex in general.’ To which they honourably reply that they used singular they on purpose because ‘we wished to conceal the gender,’ and they challenge their critic to invent a new pronoun if their politically-charged use of singular they upsets him so much. More recently, a colleague who is otherwise conservative told me that they found singular they useful ‘when talking about what certain people in my field say about other people in my field as a way of concealing the identity of my source.’

Former Chief Editor of the OED Robert Burchfield, in The New Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1996), dismisses objections to singular they as unsupported by the historical record. Burchfield observes that the construction is ‘passing unnoticed’ by speakers of standard English as well as by copy editors, and he concludes that this trend is ‘irreversible’. People who want to be inclusive, or respectful of other people’s preferences, use singular they. And people who don’t want to be inclusive, or who don’t respect other people’s pronoun choices, use singular they as well. Even people who object to singular they as a grammatical error use it themselves when they’re not looking, a sure sign that anyone who objects to singular they is, if not a fool or an idiot, at least hopelessly out of date.

Dennis Baron

Professor of English and linguistics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Baron, Dennis. “A Brief History of Singular ‘They.’” OED: A Definitive Record of the English Language, 4 Sept. 2018, public.oed.com/blog/a-brief-history-of-singular-they/

https://liberationbound.wordpress.com/2011/11/12/30/

Resources in the mainstream…

https://www.thetrevorproject.org/get-involved/

https://www.autostraddle.com/more-than-words-pronouns-pt-3-they-saidze-said-192109/

https://www.autostraddle.com/more-than-words-pronouns-pt-2-howd-gender-get-in-here-188430/

https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/gender-neutral-pronouns